As an Architect / As an Educator: In Conversation with Nader Tehrani

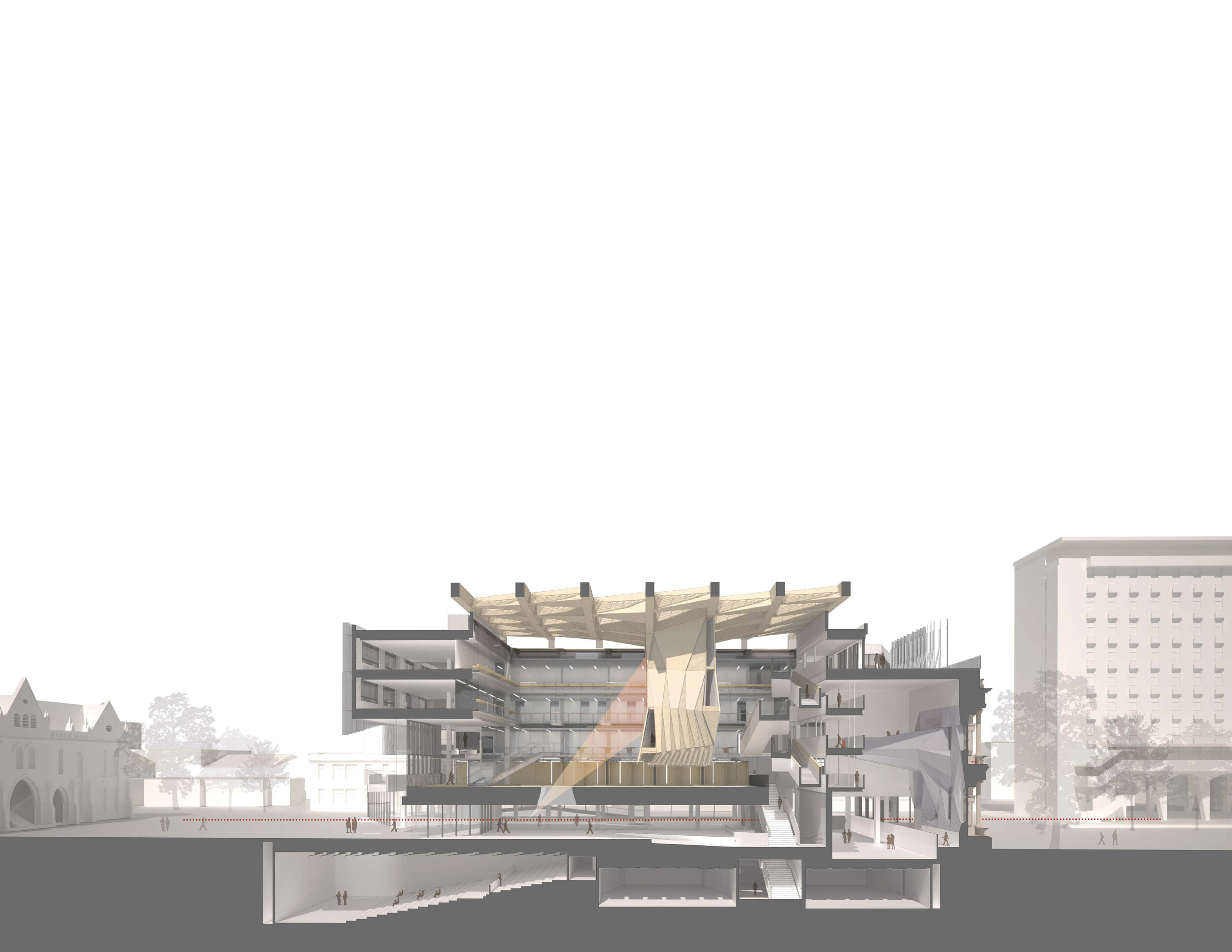

Melbourne School of Design. Photo by John Horner Photography.

Jimmy Bullis (JB): How do you, as a leader of the Cooper Union, approach guiding and providing clear direction to the school while still allowing for the contribution of other voices and advancing equality, especially as time goes on and people lose touch with the urgency of these issues?

Nader Tehrani (NT): A diminutive scale is something Rice Architecture and the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture have in common. As Dean, I represent a faculty body that is upwards of 30 people and a student body that is less than 150 people. To the extent that I insert agendas that go beyond their particular areas of interest, I am transforming the school’s culture, allowing the institution to speak to the world beyond, and imagining its potentials yet unfulfilled.

I lead in collaboration with an Associate Dean—first Elizabeth O’ Donnell and now Hayley Eber—both of whom have significant voices and counter-agendas that balance me out. Then, there are four committees that preside over key areas of governance: administration, admissions, academic standards, and curriculum. One thing I did early on was expand the adjunct faculty and student involvement in those committees, with the hope to expand their perspective. There is always an alumni member on each committee, and they tend to bring historical perspective as well as views from the profession and their personal experiences.

The other main issue to consider is the intangible—that is, the atmosphere of the school. There is a culture within studios and within faculty-student relationships and collaborations that escapes the formalities of structured participation. I have tried to redouble our efforts at organized events that move the school towards difficult questions, and all the while, radicalize our ability to improvise and take advantage of the daily things that should not require vast bureaucracies to oversee. This sensibility has probably been the most important aspect of creating an environment where people feel included, heard, and central to a project that is at once coherent and inviting of divergent paths.

One final note is that as Dean you often come to a school with a project or conception of what you want to do and it is a rare occasion when the school gives you the space to deliver on it. What you end up doing is a balancing act of improvising, reacting to situations, and fostering the school’s atmosphere. It’s not that you don't voice your own opinion—you certainly do—but the more critical thing is that you serve as a bridge between different, occasionally warring opinions. I sometimes serve as the mortar, keeping the wall together.

When I entered Cooper Union, there were only three full-time faculty members, with one leaving in my second year. This left little room for inclusion of others from a leadership perspective. Not including myself, now we have six full-time faculty members, all of whom have significant voices in different arenas. This has vastly changed the intellectual character of the daily conversations. In this sense, my administrative role as dean has become easier, which allows me to contribute in the trenches of pedagogy.

JB: I wanted to hear a little more about the curricular role that you play. There's been a lot of talk of late about the architectural canon and what we teach in architecture programs. Sometimes there’s a partial engagement with interdisciplinary and social issues that is often not fully realized within these classes, but you've been working on building the link between design work and social justice. Do you feel that there's room in architecture education for more in-depth studying beyond traditional design work?

NT: Most architecture programs revolve around the idea that we are generalists, and that enables us to draw from sociology, anthropology, urbanism, landscape, ecology, sustainability, building technology, and material sciences, among many other disciplines. Ultimately, as we design buildings we bring these things into conversation with each other and make critical choices. It is implausible to think that you can know enough in four or five years, let alone three and a half in the Masters programs. The best we can do is to develop an attitude towards learning that allows the process of revelation to occur on a continual basis, which allows us to remain students in perpetuity.

This discussion also reveals how these so-called canons come to form what people call core knowledge or fundamentals. More often than not, these are code words for Western civilization. As of late, there have been some key challenges to the cultural dominance of these canons from the Black Lives Matter movement, gender theory, and other global schools of thought whose cultures have long remained marginalized.

In the American context, the inequities of democracy have been articulated anew, pairing the advent of slavery with the constitutional foundation of democracy such that one cannot extricate one from the other. Further problematizing this is the fact that the very history we are trying to articulate lacks many of the primary and secondary sources that ought to become foundations of discourse, since historical documents have effectively shut out the voices of many during the past four hundred years. Acknowledging this and building that scholarship would be the first step in re-envisioning the history of the “other” canons. Alternatively, reconstituting histories outside the canon altogether is not unproblematic either, particularly since the idea of the canon is not limited to Western thought alone. Other cultures have also given primacy to these sets of works, whose presence within their societies is the result of a weighted relationship with power, domination, inequities of labor, and the many other phenomena that come with this discussion.

In our discussions, I don't think we have discovered any pedagogy that has found a way to balance out the amplitude of cultural differences with any depth. We have pondered approaches that are thematic or case study–based from varied cultures, while abandoning the traditional linear timeline that purports to tell a cohesive narrative, yet all tend to reveal a very partial picture of history. Still, if done with methodological clarity, a combination of these strategies offers the possibility to allow students to research material beyond their school years with a different eye towards difference, canons, and what is deemed essential.

I have always cited the Dome of Soltaniyeh in Iran; it is a double shell dome constructed over 100 years before the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. The tradition of building domes without centering is part of the history of this region and yet there is no specific historical record of communication between Iran and Italy evidencing that it served as precedent for the other. Still, its omission in the Western narrative is but one example of the limits of its partial lens. Thus, as we attempt to broaden our inclusion of cultures, histories, and geographies, we not only stand to enrich the Western lens, but also reveal a more complex story—perhaps requiring an entirely different structure of requirements within the academy.

I often refer to Fernand Braudel’s book on the Mediterranean as a good example of what it might take to look beyond architectural canons, looking beyond buildings to better understand the context within which they were conceived. For Braudel, this involved a closer observation of everyday life: communication, trade, the sourcing of materials, and the molecular aspects of cultural transmission across cultural divides. This may be a good time to rethink and extend Braudel’s project, if only to test how his methods might reveal other aspects of form, spatiality and materials that cannot be understood through other means.

JB: The idea of reforming education curriculum comes up in your statement from Fall 2020,1 and in a few conversations and writings from a number of schools. Does reform require an experimentation with different, less linear approaches to what you've been speaking about here?

NT: What is interesting about the way that the students have fashioned this discussion is that they have formed a much broader conversation about decolonization, absorbing themes into it which often do not necessarily focus on the formal, spatial, and material aspects of the built environment. They have articulated that it is not just about race: it is about multiculturalism, climate equity, gender, and a range of other social issues that impact the world today.

Looking back, many came into pedagogy with the need for and presumption of certainty. Now there is the confidence to embrace uncertainty—not only as a reflection of our changing times but as a pedagogical imperative to allow us to speculate, improvise, and rethink questions entirely. Many of the courses at Cooper right now are being tested for the first time and we have no idea what the end results might be. This is true of Lydia Kallipoliti and her explorations of “entanglements,” identifying phenomena between politics, the environment and technology, of Nora Akawi and her urban studies of erasure and exclusion in settler colonialism, and of Michael Young, whose fascination with the artifice of representation has his students drawing from the realism of certain pictorial traditions to inform unprecedented and uncanny architectural conditions.

Many of these courses draw from theory, politics, and social justice, which has the effect of not only making great architects, but well-informed citizens out of the students. Some courses may leave an arm’s length between their particular arena of research and the formal, spatial, and material implications of those debates. For this reason, one of my main questions to the academic community revolves around what the architectural discipline specifically brings to the table and how might it form our agency in a larger public conversation, whether in the halls of power, governance, or policy? How do we bring our particular mode of analysis to shed light on the policies and decisions that are made for society? There is probably not a square inch in the United States that is not the result of a spatial policy that is architectural in some way or another. When I say architectural, it's a leitmotif for landscape, geographic, and mapping policies alike, but also for building codes, zoning regulations, and other forms of restrictions that give shape to the city—all of which falls under the umbrella of this discussion.

It is a rare that architects get to sit in the seats of power and make the decisions that bring the city to life. So perhaps we should ask, “Who are we educating?” Is our target our students alone? Or are they our conduits to a larger audience of project managers, mayors, governors, presidents, and others whose capacity to understand the formal, spatial, and material can contribute back to the larger sphere of collaborations that produces the built environment? Absorbing interdisciplinarity for its own sake is meaningless if it is not paired up with a focused understanding of what it is that we do that no one else does.

Pouya Khadem (PK): As you mentioned, architects’ agency is not limited to spatial qualities but also extends into the political sphere. Many architects in the past century produced different types of manifestos, and in 2016 you similarly published a text named “A Disaggregated Manifesto.”2 What is the power of a manifesto in today's world, particularly when the criticism of ideological discourses and advocacy for collective conversation is so strong?

NT: The manifesto is a way to articulate an intellectual project. I think it is important for us, whether as students or professionals, to identify what this project is—that is, to articulate certain ideas beyond the building itself. It’s like a thesis, whose ideas need to reach beyond the project itself. Once you identify this, you have to establish its relationship with history, its connection to convention, what precedents are behind it, and with whom you are debating; you have to understand who your audience is. Finally, you have to understand how you are producing a new form of knowledge. How are you contributing to discourse?

Most of the manifestos of the 20th century are admittedly reductive, or artificially build a problem that only one architect can solve. They have often been used to construct polemics and changes in attitude. Their limited scope of view tends to be productive for provocations and the launching of debates. I titled the article “A Disaggregated Manifesto” precisely to broaden this topic—to bring it out of a monocular focus and to identify an ecology of subjects that speak to each other in more complex ways. It was also a means of documenting certain debates that have characterized the past thirty years. For instance, the reintroduction of typology as a central pedagogical device; the challenge to typology in the late ’80s; the instrumentality of the computer in enabling new morphologies in the ’90s; and our challenge in bringing questions of construction—via means and methods—as a conceptual point of departure.

Mine was a reminder that nothing is actually smooth in construction; everything is somehow mediated by labor, modularity, unitization, etc. Understanding the seam between things is much more important than understanding continuity. I was trying to frame certain aspects of a building that were irreducible, foundational, and more inclusive, often inspecting the detail as a point of departure rather than destination. The manifesto was a way to bring this history into conceptual focus.

PK: In your essay about the work of Eladio Dieste,3 you talk about the notion of the confluence of different elements into one body, a condition that seems unavoidable for architects. How do you approach the seam between the different things in architecture? Do you try to shed light on it or do you want to create a seamless whole? Does the seam carry any architectural statement?

NT: Confluence deals with the way in which disparate things are brought into conversation. In the context of Dieste, I was addressing his use of composite brick as medium, geometry as structure, and detail as a system. There are moments where I talk about the catalytic detail. Most architectural pedagogy revolves around the idea that you first come up with a big idea, and that idea gets embodied in a building scheme or a big organizational system. As you develop it, it becomes more granular until you get into construction, and then you think about the detail as the ultimate consummation of all of those ideas in a single joint. The catalytic detail reverses that thinking: the detail informs the whole, bottom-up.

When we speak of a brick wall, we never say, “let's build a mortar wall” even when we recognize that mortar is a central ingredient in the binary relationship between the two. Mortar holds the brick together, but most commonly it maintains a conceptually liminal status. We always talk about the brick as if the brick maintains primacy within that binary. Inspecting Sigurd Lewerentz’s use of mortar, we discover its wonder. It expands to such a radical dimension that the figure-ground relationship between mortar and brick appears inverted and the brick appears to levitate within a sea of mortar.

Sometimes material research unleashes the capacity of organizational systems to reveal new opportunities for tectonic systems. As such, the focus is no longer on the detail itself as an instant, but in the way a detail is distributed through a system. When you start with the seam you are really in search not of the building but of the systems underlying it, and you have to start at the seam to understand that.

PK: Your works often utilize a careful aggregation of discrete parts to express a coherent whole at a larger scale. The scale of the brick is a very intimate one. But, for instance, the scale of the expression of a fold in a brick wall is larger. I am reading this shift in scale from parts to a homogenous whole—beside the structural sensibility—as an intentional strategy to de-emphasize the structure’s deference to an individual and emphasize the collective, maybe even address a collective public as the primary audience. So, I wonder if this is an interpretation you’d share regarding your intentions with part-to-part relationships?

NT: It is. You worded it slightly differently than I would have, but I appreciate that. The relationship between the brick and the wall can be captured by the difference between the configurative and the figurative. I would say the detail has to do with the configurative aspects of bringing two things together, while the shape of the wall is about the figurative aspect. Many architects do not try to establish close proximity between the pixel-like detail and the overall shape of the building. And yet I would argue that part of the knowledge we bring to architecture is that reciprocity between the part and whole, especially under the extremities of geometric and structural play.

In tandem, the figurative legibility is often associated with the building’s capacity to communicate to broader audiences, giving it a semantic dimension and also a public one, whereas the configurative most often addresses the more detailed aspects of technical proficiency and is more accessible to the individual expert. Your question also prompts this distinction.

PK: There is a vast array of external factors involved in the translation of drawings and ideas into buildings. Might we look at this as an opportunity rather than a limitation of our field?

NT: This is an important question. Indeed, there are both inductive and deductive ways of working, and though we often think that ideas must remain pure and somehow intact during a design process, it is not uncommon for externalities to overwhelm the conceptual momentum of an inquiry. Because of this, I do agree that we must find opportunities from these limitations. Our “Sixth Elevation” lecture about the reflected ceiling plan is almost entirely dedicated to the theme of the—often forgotten—technicalities of MEP, fire safety, and structural systems becoming victims of an architectural process when not prioritized as the central conceptual issue to be tackled. In this way, BANQ, Upper Crust, Adams Library, MSD and various other projects all conspire to take on the ceiling as the catalyst for the very spaces they shelter. They do not merely solve problems, but rather extract out of constraints certain architectural circumstances that amplify the figurational/configurational opportunities latent within those spaces. Understanding how to identify externalities, translate them into architectural terms, and deploy them in such a way that transcends the problem is the key.

Nader Tehrani’s research has been focused on the transformation of the building industry, innovative material applications, and the development of new means and methods of construction, as exemplified in his work with digital fabrication. Tehrani’s work has received many prestigious awards, among which are the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Award in Architecture, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Architecture Award, and Eighteen Progressive Architecture Awards. Tehrani is also the Dean of the Cooper Union’s Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture and former Head of the Department of Architecture at the MIT School of Architecture and Planning where he served from 2010-2014. Tehrani has taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Rhode Island School of Design, the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he served as the Thomas W. Ventulett III Distinguished Chair in Architectural Design, and the University of Toronto where he served as the Frank O. Gehry International Visiting Chair in Architecture. He also recently served as the William A. Bernoudy Architect in Residence at the American Academy in Rome and the inaugural Paul Helmle Fellow at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

1 See Nader Tehrani, “A Message from the Dean | Reconsidering Our Foundations: A New Beginning,” The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, September 3, 2020, https://cooper.edu/architecture/news/message-dean-reconsidering-our-foundations-new-beginning.

2 Nader Tehrani, “A Disaggregated Manifesto: Thoughts on the Architectural Medium and its Realm of Instrumentality,” The Plan 090 (May 2016); available on the NADAAA website, https://www.nadaaa.com/office/essays/a-disaggregated-manifesto/.

3 Nader Tehrani, “Probable Architectures of Impossible Reason,” available at http://www.nadaaa.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/AR_2019_Nader-Tehrani11_smaller.pdf.